reblogged from August 22, 2016 – Deutsche Version hier

Can you starve while you still have chocolate left???

The finds at „Boat’s Place“ at Erebus Bay on King William Island and their various interpretations belong to the many unsolved mysteries of the lost Franklin expedition. During McClintock’s search for traces of Franklin’s men, on May 24th 1859 a land expedition under Lieutenant Hobson discovered a boat. Buried beneath the snow, it rested on a sledge. Hobson freed the boat from the snow load. He found two human skeletons and wrote a detailed account of the items that were in the boat.

Six days later, Captain McClintock reached the same place. Prior to that, he had worked a lot on the optimization of sled transportation on Arctic tours. In his report, he refers to the – in his opinion – „dead weight“ of the strange sled charge. There was no food left except for a small residual of tea and about 40 pounds of chocolate.

This raises the question: Is it possible to starve to death if you have 40 pounds of chocolate available? Apparently yes.

This was not the softly melting, creamy milk chocolate we know nowadays, but a product then called „Cocoa“ or „ship’s chocolate“. Roasted cocoa beans were crushed, with some cocoa butter being released in the process. The result was no dry powder, but a paste, which was cooled into a „cake“. In 1828, Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes van Houten invented a process that could separate most of the cocoa butter from the chocolate; then some of it was added again (possibly with some sago starch added) for pressing compact cake pieces that could be grated into cocoa powder.

Such hard chocolate „cake“ was part of the usual rations for Arctic expeditions because it could be used to prepare an invigorating hot drink – at that time, coffee was not yet a standard drink for expedition members! Cocoa also helped to make the unpleasant tasting water from the ship’s tanks drinkable – which helped to save rum as well. It was probably as early as 1780 that the British government had regularly commissioned solidified cocoa from the firm of J.S. Fry & Sons as a standard ration of chocolate for seamen in the Royal Navy.

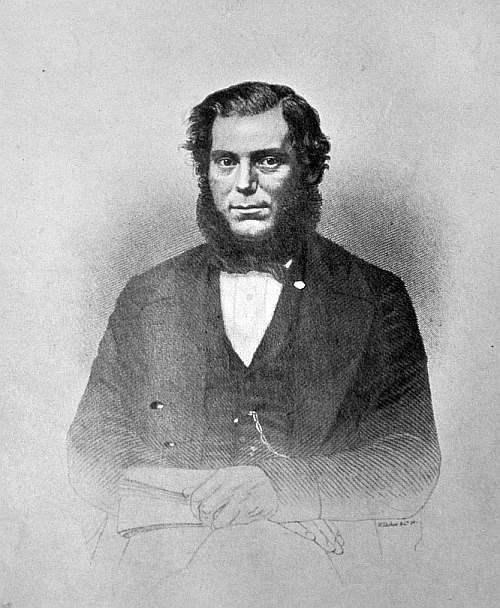

Johann August Miertsching, who took part in an expedition in search for Franklin from 1850 to 1854, regularly drank “Cocoa“ aboard HMS Investigator, which was served at breakfast. In the evening, however, tea was prepared. Coffee was served only at the very beginning of the expedition and on special occasions.

Miertsching, together with his comrades, had to leave the ice-trapped HMS Investigator in 1853 and, like Franklin’s men, they had to walk with sledges over ice and land. He describes the meager daily ration for the likewise starving men:

„1 pound biscuit, 3/4 pound meat and 1 oz. cacao plus 1/2 oz. sugar, and ½ gill rum for grog. The meat will be consumed cold and naturally hard-frozen. The grated cacao and sugar will be put in a kettle, together with ice or snow, and then cooked on a spirit stove. “ (April 15th, 1853).

So cocoa, grated and prepared as a hot drink by adding sugar and water, was likely to warm up, and due to the cocoa butter and the added sugar it even delivered some energy. But the quite bittery, hard-frozen compact mass which was found at Boat’s Place was in no way good enough to save the famished men of Franklin’s expedition from starvation. In addition to that, when taking in larger amounts of cocoa in the solid state, surely the men would have suffered from constipation.

Edit: there is a new and interesting approach to that chocolate issue, you can read it here.

In Miertsching’s Arctic diary you also can read about the usual charge of a party consisting of nine men on a sledge expedition on land or ice. Much of the objects found by Hobson on „Boat Place“ are also contained in Miertschings listing: „…brush for removing snow from the tent and clothes, boot soles, wax, bristles, waxed floss, cobbler’s wire, nails, awl, … along with soap, towels, combs etc. … pepper, salt, lighter, cotton and flannell bandage, … eyewash, pills etc., lancet, opium tincture, scissors, needles and twine; … The whole weight of such a sled charge for 42 days is more than 1,000 pounds.“ (April 17, 1851).

There has been much speculation about whether the men of the Franklin expedition were doing the right thing when they gave up the ice-trapped ships and moved to the south, thus hoping to survive and to find possible rescue. Special doubts about whether their actions made sense are arising from the many seemingly „useless“ things which the famished and exhausted men towed over land on the overloaded sled with the heavy boat. From the items mentioned in Hobsons report, in particular silverware, a signet ring and sealing wax, a golden cord, books, golden watches, soap, combs, brushes and needles are emphasized. Were these men so foolish – or even mentally confused?

Apart from the fact that those were actually not golden, but only silver cased watches: When viewed from today’s perspective, it turns out that there were quite a lot of useful and practical things in the sledge load of Franklin’s men – compass, knife, lighters, awl, waxed floss, various tools, gloves, snow goggles, powder flasks (probably with drugs), scarves, rifle and ammunition, fishing line, sewing kit, scissors, packets of needles. The things which were actually not necessary for the men themselves on their march to the south could have been possibly quite well be used in exchange to get food, in case they would have met Inuit.

Among the finds there were also some books. One can argue about how vital books are for people plagued by cold and hunger. Who can judge what value a book would have for the desperate – maybe to get some consolation, or not to lose all courage? How important can it be for people in desperate need, to create some team spirit by reading aloud from a book, or by singing a hymn together? Even about these things, you can learn in the Arctic diary from Miertsching – who, by the way, was born exactly 199 years ago.

posted by Mechtild Opel on August 22, 2016